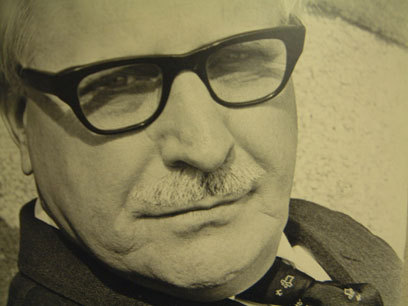

'John Creasey, Crime Writing Phenomenon'

By Simon Clegg

20th May 2014

Simon Clegg writes about the twentieth century’s most prolific crime author, and the subject of a brand new biography published this month by PIQWIQ, JOHN CREASEY, THE KING OF THE CRIME WRITERS.

I’ve dealt with some high profile names in media – both dead and alive. Here I look at easily the twentieth century’s most prolific crime author, John Creasey.

The Gideon of Scotland Yard novels stand high among John Creasey’s voluminous output, where they first appeared under the pseudonym of J.J. Marric, one of more than twenty pen-names used by Creasey. (Creasey found bookshops only had so much space under the letter ‘C’, and much of which was taken up by Agatha Christie. So he had to be creative with his pen names.) The books in the Gideon sequence are pioneering examples of the so-called ‘police procedural’ and predate by a year the appearance of Ed McBain’s 87th Precinct series in the US. Since Creasey did nothing by halves or in small measure there are some 25 books in this series alone, showing the progress of the central character from Inspector to Commander based at Metropolitan Police headquarters, Scotland Yard. Creasey also penned another and even more extensive sequence set in London and featuring Inspector West, a detective lumbered – and not ironically – with the nickname of ‘Handsome’. Ah, those were the days when policemen ticked all the boxes, and probably would dive in the river after you!

More importantly, Creasey was one of the first crime writers to understand the (ongoing) public fascination with day-to-day police work, and the dramatically-interesting way in which it could be played off against a copper’s home-life. In some respects the policeman’s lot is not so different from anyone else’s. More time is spent in the office than out nicking villains. There is a bureaucratic hierarchy to negotiate, there are forms to fill, axes to grind and hatchets to bury, all set against a background of domestic strains and anxieties. But it is the crime, large-scale or petty, which inevitably gives the books their grip. At the time, and we’re talking principally of the 1950s and 60s here, the Gideon novels seemed like the last word in realism. Furthermore, Creasey was perhaps the first major proponent of such novels dealing with more than more central crime incident, a result it is said of ‘copper friends and neighbours suggesting the earlier Inspector West novels ought to be a little more realistic.

George Gideon, or G-G to his friends and criminals, is a big man in all respects. In the John Ford film version of the very first book of the series, Gideon’s Day (Gideon’s Week was ranked in rather good company as one of the top 100 crime/mystery books ever), the then Inspector was played by Jack Hawkins. The actor’s crinkled hair, gruff manner and physical bulk fitted Creasey’s described persona perfectly. In the stories, Gideon’s arrival at New Scotland Yard sends a buzz through the building, a buzz that is half-fear, half-expectation. Like quite a few old-time and real-life coppers – Slipper, Fabian – he seems to be readily recognised not only by Fleet Street but by the London public at large. And it’s no coincidence that he shares a name with a judge from the Old Testament, for this latter-day Gideon is fierce, principled and unyielding.

Tough but thoughtful, he is merciless towards any hint of corruption in the forces although, like any good superior officer, he takes time to ask after the families of his juniors – at which their eyes light up. Despite juggling several cases at once, the Commander is capable of bringing legendary powers of concentration to bear on a particular crime. He loves London which he knows intimately, from his days on the beat, through the soles of boots. The entire city is his patch or manor, and nothing escapes his attention. At their best, the books give the impression of the ceaseless onrush of police work and, in an era before graphic forensic detail, the detail and the jargon feel plausible.

Creasey may have been a bit soft or uncritical about that resolute man George Gideon – just as Ed McBain could be sentimental about some of his police heroes in the 87th series – since he emerges as someone essentially without faults, and so less interesting than he might have been. You get the feeling that even an off-duty hour in G-G’s company might be thin on the laughter front. But there was a resolute edge to his creator too. In Gideon’s River, an abducted girl is killed by her kidnapper minutes before the police arrive. In a US procedural the cops would most likely have got there in time. In Gideon’s March, a couple who’ve just begun an unlikely but touching affair are blown up in an assassination attempt on the French President during his London visit.

So how do the Gideon or the West novels stack up against the current police procedurals? There are similarities. The spats with superiors, particularly in the case of Inspector Roger West, are reminiscent of countless threats shouted or whispered in the corridors of today’s fictional stations. The switching from case to case, which Creasey may well have originated, is now a well-worn device but one which in the hands of a skilful contemporary writer, such as Mark Billingham, can be very satisfying.

But the differences between then and now are as great, maybe greater. It’s a rare modern plod who has a home-life as contented as Gideon’s (six children at the last count). Current detectives are likely to be victims of one or more of the three big Ds: drink, divorce, depression. They may even flirt with drugs, which inevitably fill a much bigger space in crime fiction now. Crime writing in general now is a lot more explicit and gory. Creasey, working in a period when the cinema resorted to a fade-out at the first hint of dropped clothing and fist fights were conducted more or less by Queensbury rules, hinted at sex and violence, or at best sketched them in lightly. His coppers are rarely heard to swear as they move through a black-and-white London still affected by bomb damage, a world of razor-boys, forgers and dodgy car salesmen. Women don’t get much of a look-in except as wives and girl-friends. All the same the policemen are in general honourable, even righteous. As they had to be. And after a fashion, even in the most hard-nosed modern procedural, they still are.

By Simon Clegg

|